Books and Cigarettes

As a literary translator, I occasionally find myself in the privileged position to develop my own projects. I follow inspiring traces, and sometimes my search turns into something bigger. So it happened with Susan Glaspell. In spring 2022, I researched the writer’s work at the New York Public Library. Curiously, the modernist classic is hardly known in Germany due to a lack of translations. I had not known her myself – until the International Susan Glaspell Society asked me to check a translation of one of her stories. A grant from the German Translators Fund delivered me from my ignorance. Subsequently, I was able to introduce this author to German-language audiences.

Susan Glaspell (1876−1948) went to university in Iowa and worked as a reporter and journalist from 1899, publishing her first short prose pieces in magazines shortly after the turn of the century. Ten years later, her first novel, The Glory of the Conquered, appeared, followed by The Visioning as soon as 1911 and by the collection of short stories, Lifted Masks, in 1912. The publications in magazines secured her an income while she increasingly improved the short form. She was already well known, when, in 1915, an entirely new artistic horizon opened for her: together with her husband, George Cram Cook, she founded the Provincetown Players and wrote numerous plays, often appearing on stage in their productions herself.

From 1916, the troupe had a theatre of their own in New York City’s Greenwich Village. After the death of her husband in 1924, Glaspell was not able to reconnect with the group, writing only two plays after that, one of which, Alison’s House, won her the Pulitzer Prize. But she kept writing novels and short prose. Their count ran up to seventy. She composed her central themes ever more precisely: the gender roles, particularly those of women in society; but also the workers movement and socialism, both of which were enormously strong in the United States at that time.

At first, I needed to gain some sort of overview of her œuvre. Coming from a theatre background professionally, I first read up on her plays. But I preferred to first translate her prose because that would open up that genre for me as a translator. Which stories do I choose? What is available? Is there a complete list? Where can I find that? With the assistance of the experts associated in the International Susan Glaspell Society, I am able to find some answers through their publications but since Glaspell’s work is not entirely explored yet, some questions remain unanswered.

In April 2022, I spend two weeks in New York City to visit the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, where much of the material of and on Glaspell and her husband is stored. I find letters, the manuscript for a speech, and drafts, maybe of an unwritten story. Careful browsing through the documents that are brought to me upon request, and reading notes in her handwriting brings me closer to the writer. In the NYPL’s catalogue, I also find her story The Anarchist – His Dog, and I hope for once to come across a manuscript or original material. This book, however, is kept in a different part of the building. I need to cross the hall and both of the large public reading rooms to reach the George Arents Collection.

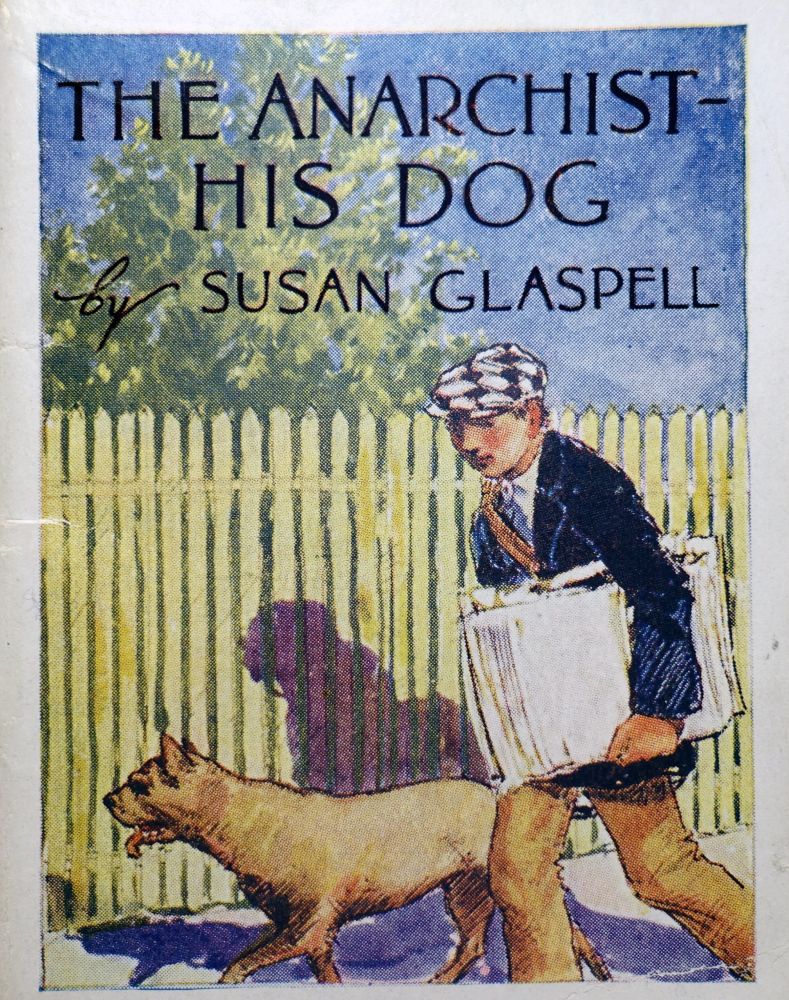

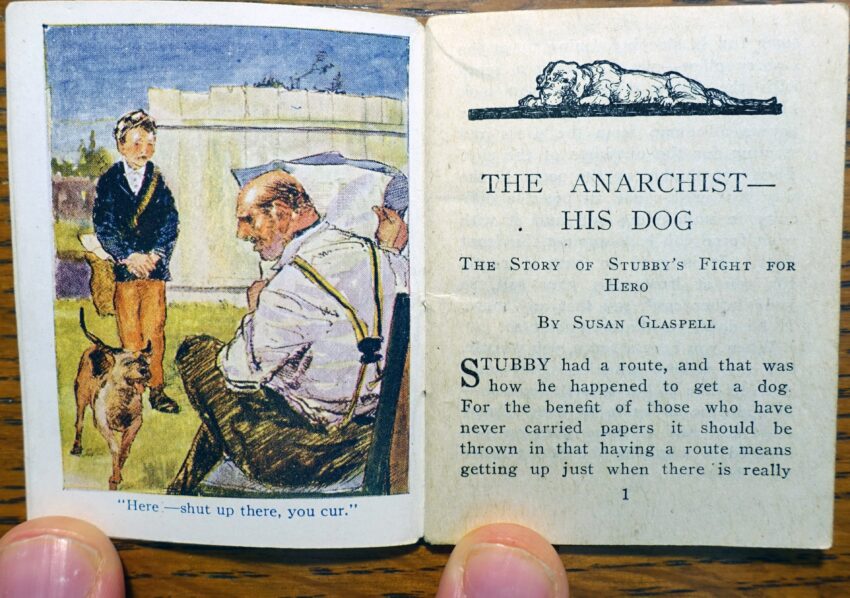

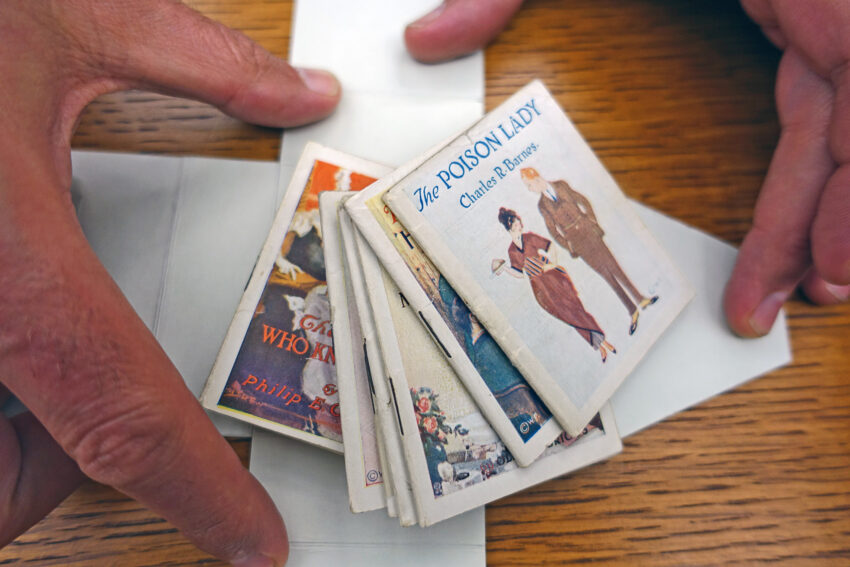

The young librarian is a good-humored, enthusiastic man who produces the story that I had reserved in advance from a backroom. I am asked to make myself comfortable at one of the long reading tables. Shortly after, the man approaches me, carefully placing the requested item on the surface in front of me. It turns out to be a tiny booklet, about the size of a matchbox. The cardboard cover illustration displays the face of a boy. I already know the story, so I recognize this to be Stubby, the protagonist.

The story: Stubby, the child of poor parents, has to earn money as a paper boy. He and the other boys have to get up very early, retrieve their newspapers and ride their bikes along their routes so the subscribers can read the paper at their breakfast tables. On their routes, the boys are not only followed by people’s dogs but most of them have their own dogs to keep them company. Not so Stubby. But at some point, a stray dog finds him.

He decides to keep him, and they become very close friends. And a friend is exactly what Stubby needs. It is therefore particularly callous when the newspaper-reading father warns his boy that there is an annual dog tax of two dollars. If you fail to pay that, the dog will be taken away from you. Shellshocked by these brutal realities, Stubby spends a few difficult days of inner conflict. Then he decides to earn the money for the dog tax himself, and secretly at that, because he is supposed to hand over every cent he earns to his parents. Despite his greatest efforts, however, he is unable to gather the required amount. Finally, Stubby learns, from his father, a bit about anarchists. These indiviuals, his father explains, are against the law, and they shoot policemen too. Right away, Stubby recognizes himself in this description. He will have to kill the policeman who will take his dog. But being a good boy, Stubby writes a letter to the officer warning him that he will have to kill him if he were indeed to take his dog away from him. And it would not be a Glaspell story if the ending had not a surprise twist to it.

Susan Glaspell wrote that story in 1914. Like many of her narrations, it could be used as a model for the composition of a short story, and I presume that that has already been done. In Dem Anarchisten sein Hund, which will later be the title of my German translation, Glaspell mobilizes her rich arsenal of empathy and humor to unfold the plot around the young protagonist and the obstacles he has to overcome. But I wonder – why does Glaspell write about anarchists, of all people? I know that she often wrote her stories inspired by real events. Let’s see: by strict parental and then legal domination, the boy finds himself hard pressed for radical measures. (She plays with this trope in a very different manner in her story A Matter of Gesture, which is not funny at all.)

Rereading the passage, I find that the young protagonist overhears this expression from his father who reads it in his newspaper. What kind of newspaper, I wonder, will that destitute man have read in his small home in the United States in the early years of the 20th century? Is it a workers’ gazette? And what will it have had to say about anarchists? Regarding acts of violence against the state: If the story takes place in the year of its publication, it could refer to the assassination attempt by Gavrilo Princip on the heir presumptive to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie Chotek, duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo. Princip, however, a member or stooge of the nationalist, pro-Serbian, secret terror league Black Hand, was anything but an anarchist. It is, of course, a different matter what American newspapers would make of this.

More likely, Glaspell refers to the history of the anarchist movement in the US that had been creating a spectacular stir during the thirty years before, at the latest with the Haymarket events in Chicago on 1 May 1886. Here I stumble upon an exciting, almost forgotten story. I realize that the beginning of the labor movement in the US overlapped with Glaspell’s adult years. The radical left labor movement in the US and Susan Keating Glaspell practically grew up together. Glaspell was familiar with these circles – the broad community with its many radical, German-language magazines and papers, bearing iconic names like Freiheit, Die Autonomie, Der Vorbote, Die Fackel, Freie Arbeiter Stimme (in Yiddish), Die freie Gesellschaft (also in Yiddish) and many more, which is of special interest when translating Glaspell’s stories into German. But how does this story end up in the Arents Collection? And why the hell did it appear in this droll format?

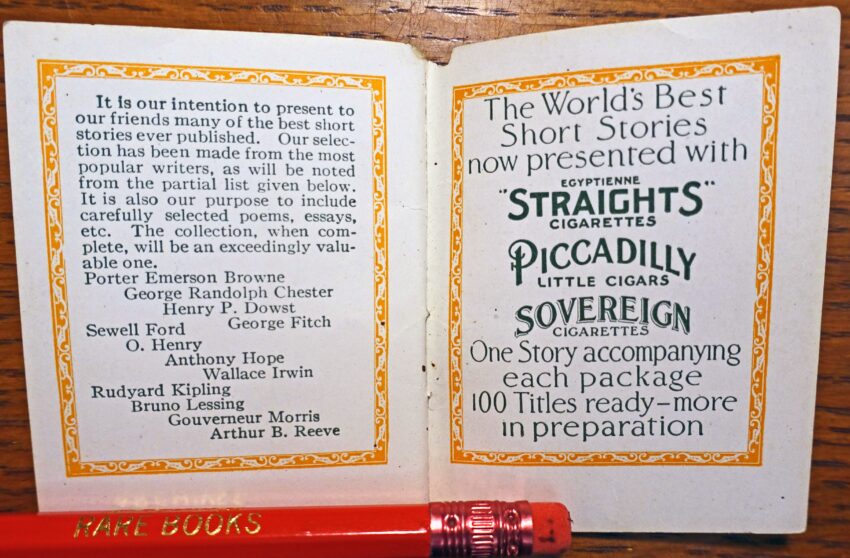

After having dealt with the good piece of prose intensely, I pester the librarian with question he answers very willingly and in detail. In 1914, Winthrop Press in New York prints a collection of thirty-three of the best short stories of the time for the American Tobacco Company. Apparently, there were plans to publish one hundred texts but, in the end, there were only thirty-three. Which is not bad either. The library catalogue offers plenty of information on this campaign: the story is listed here as part of the item with the catalogue number S 1851, the American Tobacco Company being tagged as additional author. Each individual booklet is listed as “Arents S 1751 no [1-33]”, The Anarchist – His Dog being number 13. “31 pages, collector’s item, 71×55 mm.” The American Tobacco Company had it printed in a special edition in the form of these miniature books. But why? The knowledgeable librarian enlightens me: they were packed with cigarette boxes of the Egyptienne Straights, Omar, and Sovereign brands as well as with the Piccadilly Little Cigars as premiums.

I imagine how the chain-smoking advertisement makers à la Mad Men became increasingly bored with the collectors cards of famous baseball players (listed in the American Card Catalogue of the library as well), and of the nice little satin flags that were packed with the Egyptienne Straights for a while; how they sat around their vast office space, smoking, and could not think of convincing ideas for new advertising campaigns and therefore picked up a paper or something in writing lying around to take their mind off the task, and how they felt good about being distracted like that. Apparently, smoking-while-reading was a common thing. There is even a great essay by George Orwell from 1946, entitled Books vs. Cigarettes, in which Orwell compares the cost of reading with that of other edifying pastimes like smoking, drinking, and the movies.1 And then one of these guys jumps up, always smoking, and says with both excitement and focus, pointing with both cigarette-holding fingers into the air or at his colleagues to emphasize his thought even more: What if we were to turn that around? Everybody looks puzzled. Why don’t we, along with the smoking pleasure they pay for, give people free reading that they are (according to Orwell) too stingy to pay for?2 Enthusiastic applause from the team. To have the tobacco industry, never shy about implementing offensive strategies to create addiction in order to raise their profit, propagate reading-while-smoking, is, in its subtle shift of accent, an admittedly original idea.

Seeing me impressed, the young man behind the counter briefly lets his words sink in. Then, with a “please wait one more second”, he disappears in the back again. When he returns, he presents, adequately proud, a box containing the entire collection, the full series of these booklets. The librarian’s colleague, the competent man explains, had custom-made these three cardboard boxes and their stylish sleeve to store the thirty-three specimens, eleven a piece. Among them, I see, despite the small print, many classics at first glance: Rudyard Kipling’s The Taking of Lungtungpen, Edgar Allan Poe’s A Cask of Amontillado, O. Henry with The Ethics of Pig. The Headless Hottentot byJerome Beatty makes me curious. Among the two women (the other being Olive Mary Briggs), Glaspell is represented even twice, because number 12 in the catalogue is the story According to His Lights, a title I am not yet familiar with.

I agree, it is a stout collection, and quite remarkable, both the collection and the boxes. So much beautiful literature that had to be well-known and slim in stature, too, gathered in such compact space, is a charming gem of the Arents Collection and allows for enlightening insight into an era long gone by, when the delight of consuming highly carcinogenic neurotoxins could be coupled with generally more laudable pleasures. In Germany, advertisement for tobacco products was limited only very slowly, much slower than in other European countries, thanks to successful lobbying. Wherever I see cigarette boxes today, they stare back at me with morbid imagery. I have to quickly avert my gaze every time because the ulcers and destroyed organs make me choke. I am deeply astounded by the attempt to make a tar lung appear appealing to people by virtue of high-caliber literature – that is undoubtedly a remarkable marketing success.

As a translator, I enjoy this work of making a find, researching, and developing a publication project. As a next step in this project, I translated two sample stories, and in 2022, I was lucky enough to raise the interest of Sabine Dörlemann, committed Swiss publisher specializing in modernist writers. It is a perfect match. Another grant from the Translators Fund covered the translation costs. I spent the following months compiling a selection of stories, translating them, and adding a postscript for the readers’ orientation. In September 2023, I published it with Dörlemann under the title Die Rose im Sand. There, you can read the story Dem Anarchisten sein Hund now – in German.

- „it looks as though the cost of reading, even if you buy books instead of borrowing them and take in a fairly large number of periodicals, does not amount to more than the combined cost of smoking and drinking.“ (Orwell, Books vs. Cigarettes, Mass Market Paperback, 1946) ↩︎

- „at least let us admit that it is because reading is a less exciting pastime than going to the dogs, the pictures or the pub, and not because books, whether bought or borrowed, are too expensive.“ (Orwell, Books vs. Cigarettes, Mass Market Paperback, 1946) ↩︎

➽ This article was first published in German on TraLaLit, on 12 June, 2024.

➽ A slightly abridged version of this article was also published on the website of the International Susan Glaspell Society.

Images sources: Glaspell, Susan. The Anarchist — His Dog. New York, c1914, Winthrop Press. Call number: Arents S1751 no. 13. Rare Book Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Fotos: Henning Bochert

[…] Books and Cigarettes […]