Theater Translation as Creative Process

Report on the conference with the same name at the UNC in Chapel Hill in October 2019

When is theatrical translation a creative process? What challenges do translators face in a theatrical context? What opportunities do they pursue, what obstacles do they encounter?

The second conference with this title at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill gathered theater translators and professionals from related disciplines for four days to discuss such questions (10-13 October, 2019). The conference was hosted by Adam Versényi, editor of THE MERCURIAN and head of the UNC drama department, who had already hosted the first conference in 2012. Four staged readings of plays translated from Korean, German, Spanish and Italian, whose translators had been invited to talk about their work, provided rich examples to focus conversation.

With IPLAY by Austrian playwright Bernhard Studlar, translated by Henning Bochert, the debate mainly centered on the unusual format deviating from the realistic convention: The “text app” structured into 100 units offers no discernible plot or even characters. What were the circumstances under which this play was developed? Are all plays of this playwright shaped the same way? Why did he choose this format? In translating this text which oscillates between the banal-comical and the poetic, it was primarily the rhythm that needed to be tackled. The different registers of the various text genres (dialogue, poem, slogan, fictitious URL, journal entry…) called for equivalent solutions in English. The humor of the play was a sure hit, even the subtle melancholy and the criticism towards alienation in capitalist systems resonated with the audience. Critical observers remarked that the format had exhausted itself after two thirds of the duration. Director Joseph Megel and the cast (Elisabeth Lewis Corley, Christopher Chiron, Lormarev Jones), however, had decided not to follow the playwright’s invitation to take whatever liberties they felt inclined to, given the conference context and their wish to foster discussion of all facets of the text. With IPLAY, we were also able to refer to the use of lists as a reference to the infinitude of the subject in the theater context that otherwise aims at condensing, as Jonathan Kalb explains in his preface to his book GREAT LENGTHS. In a conversation prior to the conference, Studlar remarked that the play had been written in 2013 as a reaction to the then more fashionable “directors’ theatre.” The ensuing discussions focused on the differences in the essential and significant relationships among playwright, text and direction in various theatre cultures and contexts.

Sam-Shik Pai’s INCHING TOWARDS YEOLHA, translated by Walter Byongsok Chon, presented a satirical fable about an isolated, fictitious village in a timeless past. The broad cast, presenting every member of the village community, nonetheless presents rather stereotype characters. While the western audience was able to roughly follow the plot of the long play, the many character motivations and references remained largely obscure until the translator explained the historical hints in the title and the character names. A brief introduction to the history of the Korean language facilitated an understanding about its inherent capacity to indicate a hierarchy predominantly linked to seniority but also to gender that is very important in Korean society. Korean offers precise formulas of address and politeness that immediately make clear who is talking to whom and what their respective status is. The humor in the play, for example, is based on improper use of language, i. e. the implicit questioning of these hierarchies. Walter described his efforts to find appropriate solutions for these fine differentiations in English where this terminology does not exist. Historic allusions to names and places got lost (for instance, references to a journey taken by a writer of the Joseon dynasty to the Chinese Qing Empire). This sparked the old question of whether and how cultural differences and backgrounds of this dimension are even translatable. Very soon, the term adaptation was on the table: Must, can, may references based on cultural knowledge which can’t be presumed with a different audience be replaced by other corresponding solutions known in that culture? (Directed by Aubrey Lynn Snowden, with Aurelia Belfield, Kathryn Brown, Steve Dobbins, Marcia Edmundson, Sarah Keyes, Anish Pinnamaraju, Gage Tarlton, Patrick Weeks.)

“Sarajevo: Writing and Translating a City in Wartime“ – this was the title of a discussion about translating plays and themes from ex-Yugoslavian countries with our colleague Paula Gordon and prose translator Ellen Elias-Bursac, organized by the CSEES, the “Center for Slavic, Eurasian and East European Studies“ at UNC. Ellen is a renowned literary translator and incoming president of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA); she translates, among other things, plays by Almir Imširević. She and Paula discussed with Adnan Džumhur, Associate Director of CSEES, how they found their way into translating and their relationships with writers in the Balkan states. Unfortunately, the participants were unable to attend a reading of a translation by Ellen that took place the same evening as the first reading at the conference.

That afternoon, the participants introduced organizations in which they are active: Theatre in Translation Network (TinT) (Neil Blackadder) – a network to promote translated plays in the US; Language Acts and Worldmaking (Sophie Stevens) – a research project on learning foreign languages and the mutability of languages; Drama Panorama: Forum für Übersetzung und Theater (Henning Bochert) – an organization for theatre translators; The Fence (Jonathan Meth) – a network of international playwrights and theatre makers; Laertes Books (Nina Kamberos) – a US based publisher for translated theatre plays. The latter received special attention since the opportunities to have playscripts (particularly from other cultures in translation) published in print are severely limited in the US. This is hardly any different in Germany, while in France, for instance, print versions are quite common.

That Jacqueline E. Bixler, translator of HOTEL GOOD LUCK by Mexican playwright Alejandro Ricaño, was unable to attend the conference was a pity because the play (directed by Jeff Storer, with Bobby Derrick Ivey and Larry Michael Foley; Sound: Edward Hunt) was very well received for the poetics of its existential questions of life, death, loss, and time. We follow the text – almost a monologue, yet occasionally the character of a friend appears (the “witness to life” (Jonathan Meth)) – and the protagonist on their enigmatic meandering – often reminiscent of Murakami’s early surrealistic writing – through refrigerator portals into universes in which the dead are only alive to die again. The big subjects and emotions are delivered with a refined virtuoso humor related to the absurdity of the plot. Certainly, had Bixler been able to join us, this and the playwright’s work would have generated a compelling discussion.

The fourth play DUST, a two-hander by Italian playwright Severio La Ruinas’s about an abusive heterosexual relationship in Thomas Haskell Simpson’s translation (directed by Adam Versényi, read by Tia James and Jeff Cornell) didn’t leave much to ask for in terms of refined reading. Most of the spectators, however, felt that the play itself was jaded and under-complex, the presentation of the relationship and the increasingly transgressive behavior on the part of the man as well as her passive stance were perceived as unsatisfactory and conventional. The translator, talking via Skype from Italy, reported on the language of the play and that the playwright had written his earlier plays exclusively in Calabrese dialect. For DUST, he decided to opt for an almost sterile language that lets the words appear harmless while the actions and intentions of the man in the play are painfully intrusive.

Talks among the participants in the course of the conference repeatedly touched the translators’ collaboration with the playwrights. The writers generally enjoy the conversations that, thanks to the uniquely close attention translators devote to the text, more often than not render valuable insight into their own texts. Occasionally, however, playwrights seem to find the idea of having their plays translated uncomfortable or alienating since they deem their plays to be so intricately woven into and out of their original language that they didn’t see how the texts could be the same plays in a different language.

The translators of plays from the Spanish Golden Age did not share this experience or this problem; Gary Racz (LIU Brooklyn, NY) and Ben Gunter (Theater with a Mission, FLA) were rather concerned with questions regarding format, rhymes and meter. How contemporary may the humor be in translations of such historical plays?

Another interesting discussion developed around standards of notation, around ellipses (…), the dashes (-), “silences”, “pauses”, “beats” and their meaning in the respective circumstances of our work; are they different in other cultures? And what to watch out for when translating more gesture-inclined languages (e. g. Italian) the body language of which is often implicitly written into the text, making the “embodied word” (Patrice Pavis) particularly meaningful? How to deal in translation with grammatical and social gender, which have very different effects and manifestations in different languages?

The theoretical questions became very practical in cold readings of translations in progress. Paula Gordon read the first scene from her translation of Ljubomir Đurković’s REFUSE (STUFF AND NONSENSE ABOUT FATHERLAND AND FAMILY IN THIRTEEN SCENES) (OTPAD (OTADŽBINSKO-PORODIČNE TRICE I KUČINE U TRINAEST SLIKA)), Ben Gunter presented a section from AUTO DE LOS REYES MAGOS from the 12th century which is considered the first Castilian and Spanish play. Dan Smith presented a scene from the very funny melodrama THE HORRIBLE EXPERIMENT (L’HORRIBLE EXPÉRIENCE) by the Prince de la Terreur of the 1920s, André de Lorde.

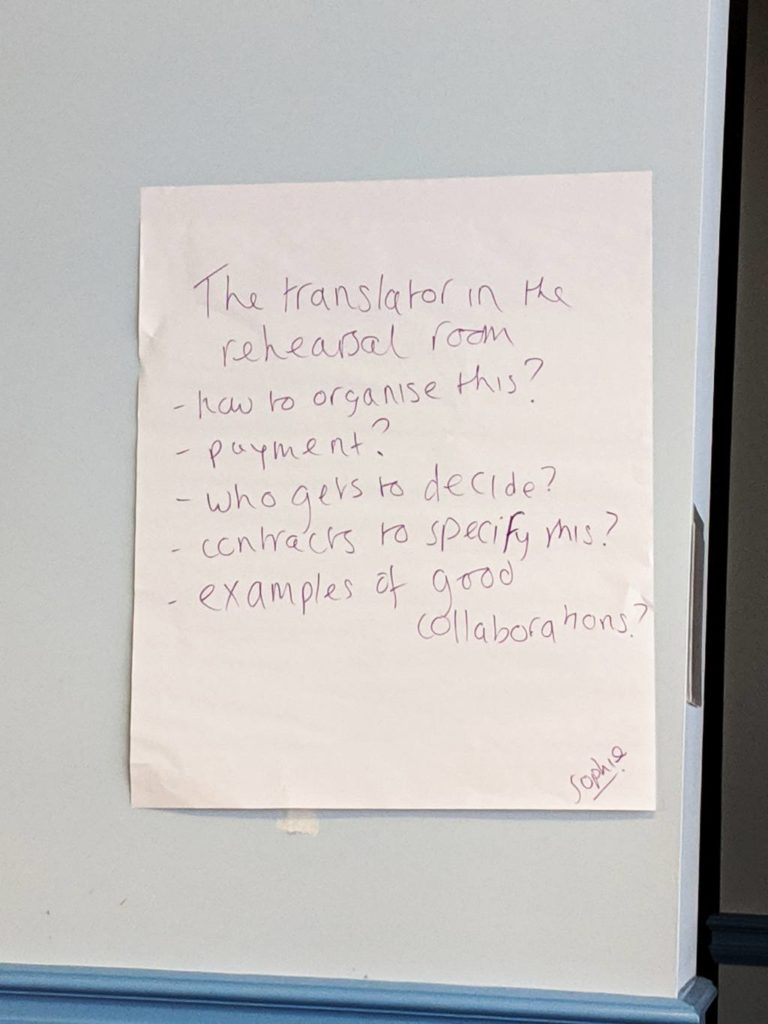

Particularly in the U.S., translators ask themselves: How to get theaters to produce translated plays? How can we succeed in persuading theatres to treat new translations as new plays? And how do we then get the translator into the rehearsal room? Which journals or media cover theater in translation? How best to keep the conversation begun in Chapel Hill going?

Differences in translation practice became very obvious once we discussed the various contexts and systems we work in: our translations turn out differently depending on their production conditions. It is one thing to translate for a publication, i. e. an audience of readers, and another – as is true for most of the American colleagues – to translate for a concrete production where they may then be invited to be part of the rehearsal process, too; and it is yet another thing not to know what production the translation will be used for – as is often the case on the German market, where translations are mostly commissioned by literary agencies so the translator needs to keep her decisions open to allow for many interpretations and to keep in mind and trust that she will not be the last hand touching the text in a “delayed teamwork” (Christoph Hein). I envy my colleagues at UNC their experience of being welcome in the rehearsal process and the opportunity to finalize their translation in a production: a beautiful plan and my wish for the future.

Leave a Reply