Playwrights elsewhere: Belgium (Dévillé)

Published on 5 August, 2015 on EURODRAM

HITLER IST TOT (HITLER IS DOOD)

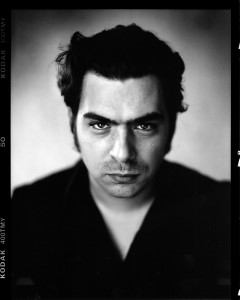

by Stijn Devillé

translated from Dutch by Uwe Dethier.

The play HITLER IS DOOD (Germ.: HITLER IST TOT) by Devillé describes the situation at the trial against the main war criminals in Nuremberg in 1945/1946. For the playwright as well as historically, this situation is largely defined by the eponymous fact that the auratic era of the “Führer” is over after his suicide. His two most important deputies, Goebbels and Himmler, also have themselves „van het leven beroofd“, i. e. taken their lives, as it is put on the playwirght’s Internet page. The large cast of the play consists of the remaining leading troupe of the party kept in Nuremberg and the persecutors, judges as well as one female jouralist.

The play is mainly characterised by its heavy topic that completely focusses on the characters. Dialogues are short, dynamic, the atmosphere is dense. The notation is also worth mentioning. As he did in his first play HEBZUCHT (GREED, translated into German (HABSUCHT) from Flemish by Uwe Dethier), which presents a family during the financial crisis, Devillé notes the text in table format, with the character names on top of the page and the dialogue cascading below.

The play is documentary insofar as the some of the characters are historic. The persecutor and the press are fictional. The written documentary format is currently not much en vogue which makes this exception noteworthy, on the other hand there has been – apparently and surprisingly – so far no play been written about this special situation after WWII.

One thing are the arresting historic individuals and their behaviour in the context of the trials that displayed all features of a theater production when they happened. But then the scenes with the prosecution and the judge, obviously quickly recruted from nowhere, how insecure their pisition was against heavyweights like Göring or Streicher. Although the institution of the International Military Court was backed by UN resolutions and as such continued and extrapolated international law. For the first time, however, the representatives of an at the time souvereign state were made responsible for their actions which then indeed led to problems in the prosecution’s argumentation, consolidating the position of the defendants.

Dear Stijn Devillé, what made you write this play?

Many of my plays raise questions of morality: what is right, what is wrong? In 2002 I wrote a play dealing with the life of my uncle. He was a hero of the resistance in the Second World War, but later, in the 1950s, he was involved in an anti-communist task force that killed the Belgian leader of the Communist Party.

So the war hero became a common killer. When this came out in the late nineties, I was shocked. (It was only in 2007, a few months before his death, that my uncle admitted killing the party leader). It seemed to me that there was no such thing as right and wrong: there are always thick grey areas in between.

The Nuremberg trials seemed like the mother of all cases tackling this eternal question between right and wrong. It was clear to everyone that the Nazi state was wrong, but did that automatically mean that the Allies were right all along? And what might the consequences be for future generations? As a child, I always had the feeling that I was born “on the right side”. But with what right could I claim that? On the contrary, by being born in 1974, I became a part of humanity responsible for a holocaust: humanity had no way of erasing this stain from its history. As if we were all touched by this “original sin”. That’s why Edith Berger says in the last scene of the play, “We didn’t win the war. We lost it.” This point of view made this historical case very relevant, obvious and modern for me.

Which source did you use?

In the run-up, I had spent about five years researching (while writing and directing other projects) and another year full time. The main source was the original transcripts of the Nuremberg hearings: they comprise 47 books. These transcripts have been made publicly available on the internet through Yale University’s Avalon Project. Other important sources were: INTERROGATIONS: THE NAZI ELITE IN ALLIED HANDS, 1945 (2001) (VERHÖRE: DIE NS-ELITE IN DEN HÄNDEN DER ALLIEDEN 1945, Ullstein Taschenbuch 2005) by Richard Overy, THE NUREMBERG INTERVIEWS: CONVERSATIONS WITH THE DEFENDANTS AND WITNESSES by Leon Goldensohn & Robert Gellately and the NUREMBERG DIARY (NÜRNBERGER TAGEBUCH, dt. by Margaret Carroux, Karin Krauskopf and Lis Leonard, FISCHER paperback 1977) by Gustave M. Gilbert. Both Goldensohn and Gilbert describe the behind-the-scenes trials, but Gilbert is very biased, while Goldensohn (in the edition by historian Prof. Dr. Gellately) is more accurate. The scenes with Albert Speer are adapted from the work of Joachim Fest. There were also works by Steffen Radlmaier, Bradley F. Smith, Norbert Ehrenfreund, Hannah Arendt, Viktor Klemperer, Ian Kershaw, Geert Mak, Jörg Friedrich, Martha Gellhorn, Gitta Sereny…

While the German defendants are historical, the Americans and English seem to be fictional in the play. Why?

All four characters (Robert Jackson, Dodd West, Rebecca Goldensohn and Edith Berger) are remotely based on historical figures. But since they were little known to the public (Thomas Dodd? Airey Neave?), I was able to make them different:

I wanted to distinguish between the defendants on the one hand, who could only think and argue about their past (there was only death ahead of them), and the accusers on the other, who also had to deal with the future. So in order to make the play relevant for today, it occurred to me that it would be exciting to make these characters very young. About my age. Historically, that wasn’t quite accurate: Robert Jackson, for example, was over 50 in Nuremberg, but in our version he was played by an actor in his late twenties. How do young people deal with this problem of having a whole life, the whole future still ahead of them?

At the same time, this gave me more artistic freedom: I could describe habits and inclinations that prevailed in Nuremberg at the time (e.g. free sex; or a rather lavish and permissive atmosphere with regard to drinking and alcohol) without having to pay close attention to whether this or that historical accuser would have participated in such permissive evenings in the hotel lobby…

The character of Edith Berger is based on several historical women who were present at the trial, e.g. Martha Gellhorn, Rebecca West, Elsa Triolet and Hannah Arendt. Rebecca West, for example, had an affair with the American judge Francis Biddle during the trial, hence the liaison between Dodd West and Edith Berger in the play.

By the way, an interesting book has been published on the subject of simultaneous interpretation at this event: SIMULTANDOLMETSCHEN IN ERSTBEWÄHRUNG: DER NÜRNBERGER PROZESS 1945 (Schippel/Kalverkämper, Frank & Timme, ISBN 978-3865961617).

Uwe Dethier is a translator from English, Dutch, Flemish and also from Bernese German. He has translated numerous plays by authors such as Roel Adam, Ignace Cornelissen, Guy Krneta and Charles Way, many of them for young audiences. The plays by Stijn Devillé that he has translated are not yet represented by German-language publishers.

Der flämische Autor Stijn Devillé verzeichnet auf seiner Website www.stijndeville.be 10 Theaterstücke, von denen die hier erwähnten zwei ins Deutsche übersetzt sind. Er ist außerdem Theatermacher. Nach Braakland/ZheBilding in Leuven, Belgien, ist er seit kurzem Künstlerischer Leiter eines neuen Hauses: Het Nieuwstedelijk.

The Flemish author Stijn Devillé lists 10 plays on his website www.stijndeville.be, of which the two mentioned here have been translated into German. He is also a theatre maker. After Braakland/ZheBilding in Leuven, Belgium, he recently became artistic director of a new house: Het Nieuwstedelijk.

Would you briefly tell us something about this new venue, Mr Stijn?

Het nieuwstedelijk is the new municipal theatre of Leuven, Hasselt & Genk. It is the result of an amalgamation of Braakland (my company, which was chosen as the city theatre of Leuven in 2010) and de Queeste (the small city theatre of Hasselt). We aim to produce new plays that ask questions about life and society in the twenty-first century: what is happening in our cities, in this world, and what impact does that have on our everyday lives? I am currently working on a trilogy on the banking crisis and the resulting euro crisis, HEBZUCHT, ANGST & HOOP.

HEBZUCHT (HABGIER, also translated by Uwe Dethier) premiered in 2012, ANGST in 2014, and HOOP (HOFFNUNG) comes out on 3 December 2015. The whole trilogy will be shown in one piece in spring 2016.

Leave a Reply