100 Years That Shook the World

translated from German by Kate McNaughton

A series of theatre events by the Theatre of Generations (Театр Поколений) to mark the 100th Anniversary of the October Revolution in St Petersburg, 06.-16.11.2017

Despite being one of the most globally significant events of the past century, the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia is not officially discussed in the Russian Federation, the state that replaced the Soviet Union which the Revolution had created. This is connected to Russia’s consciously vague and distant attitude to history, which might be summed up as follows: Russia has had more or less impressive periods in its history, but has always been a powerful state with a decisive influence on the world stage. A more sophisticated exanimation of an event such as the Russian October Revolution, which represents a sharp turning point between two such periods, would require the country to undertake a critical self-examination, which would necessarily have unwelcome consequences for its current political class. This is why the authorities tend to avoid the issue.

The Theater of Generations (Театр Поколений) in St Petersburg has been working for years on developing a more sophisticated approach to political issues. This is one of the reasons why the theatre was interested in becoming involved in a coproduction with the Berlin-based association Drama Panorama: Forum für Übersetzung und Theater e. V. (Drama Panorama: Forum for Translation and Theatre). The play that resulted from this cooperation – 67/871-LENINGRADER BLOCKADE (67/871 – THE SIEGE OF LENINGRAD) was supported by “Erinnerung-Verantwortung-Zukunft” (“Memory-Responsibility-Future”), a Hamburg-based foundation, and had its first showing September 2017 in the Theater unterm Dach in Berlin. The siege of the city of Leningrad (which now once more goes under the name of St Petersburg) by the Wehrmacht for 871 days claimed over a million victims due to starvation. In Germany, people are barely aware of this war crime, whereas Leningrad was named “City of Heroes”, and kept this title when it was renamed, just like it kept the extremely grand, monumental memorial to the “heroes” of the city – people who Stalin left with no other choice but to starve, before he elevated them to the status of heroes. Forgotten in one country, and idealised in another – it is this difference which captured the imagination of the theatre-makers from both countries who were involved in this production.

The anniversary of the Revolution also gave the Theatre of Generations a further impulse to theatrical (re-)action. John Reed’s famous book, TEN DAYS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD was the inspiration behind the title of their piece, СТО ЛЕТ, КОТОРЫЕ ПОТРЯСЛИ МИР. From the 6th to the 15th of November 2017 – dates loaded with historical significance – the ensemble worked – with a rotating cast and under the direction of “commissars” – on a theme defined and stage-designed by artistic director Danila Korogodsky, and gave a public performance of the result every evening. The theatre, which has been described by Thomas Irmer in Theater der Zeit as “one of the most important independent theatres in Russia”, has developed a fruitful habit of regularly collaborating with international guests. As part of the present series, the theatre invited Christopher Barreca, Head of Scenic Design at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), who had already been involved in several productions, as well as historians such as Ivo Mijnssen, from Switzerland, or Grischa Meyer, from Berlin, international puppeteer Yulya Dukhovny, the St Petersburg-based choreographer Darya Barabanova and the Berlin-based author of the present article. German theatre director Eberhard Köhler has long been part of the management of the theatre. This production brought a handful of puppeteers and interested actors together on the stage, to which were added any available actors from the Pokoleniy ensemble.

Every morning in the theatre on workshop days started with the technical team being told what the space needed to look like, while the performers were usually divided up into groups and assigned different tasks, in order to make the most effective use of the hours left before the evening. They developed material, and showed their suggestions to the “commissars” in the late afternoon or early evening, at which point the directorial team, consisting of Dukhovny, Köhler, Barreca and Korogodsky, would give them critical feedback; and in the evening, they gave a public performance. Thanks among other things to the performers’ excellent improvisation skills and the involvement of the group of puppeteers, this created highly heterogeneous performances that were well worth seeing.

The fact that the former factory floor on Lakhtinskaya was sold-out every evening with between 50 and 60 audience members is remarkable for several reasons. The first thing that might surprise you is that both the audience and the performers were mostly young people, i.e. between 25 and 40 years old – something which cannot be said of the demographics of German theatre-goers. In addition, there are around a hundred theatres for audiences in St Petersburg to choose from, so that the fact that audience members even went to the trouble of making their way to the theatre during this wet and cold week in the city at the mouth of the Neva river is made all the more astounding by the fact that they had as little idea as the people involved of what they were actually going to see, since the content was only put together on each day, and often wasn’t yet set in stone even ten minutes before the doors opened.

From a thematic perspective, the work explored issues around the themes of glorification and hero worship, commemorated the huge suffering caused by Stalin’s rule, and explored lost and new utopias, and the question of utopias in general.

In his lecture, Ivo Mijnssen offered a historical overview since the October Revolution, explaining the impacts and consequences it had throughout the 20th century, the images and hope which people connected to revolutions and the idea of revolution, and described our present day as an era of conservative revolutions.

In his illustrated presentation, Grischa Meyer compared the different iconographical readings and meanings of Kazimir Malevich’s famous painting “Black Square”, today and at the time it was created. He put forward the thesis that, unlike today (and as it is today assumed was the case at the time it was created), the “Black Square” was in fact at the time a sign that was very easy to read, and was not primarily perceived as an abstract, theoretical sign, but rather as a form filled with a concrete meaning as a result of its iconographical origins.

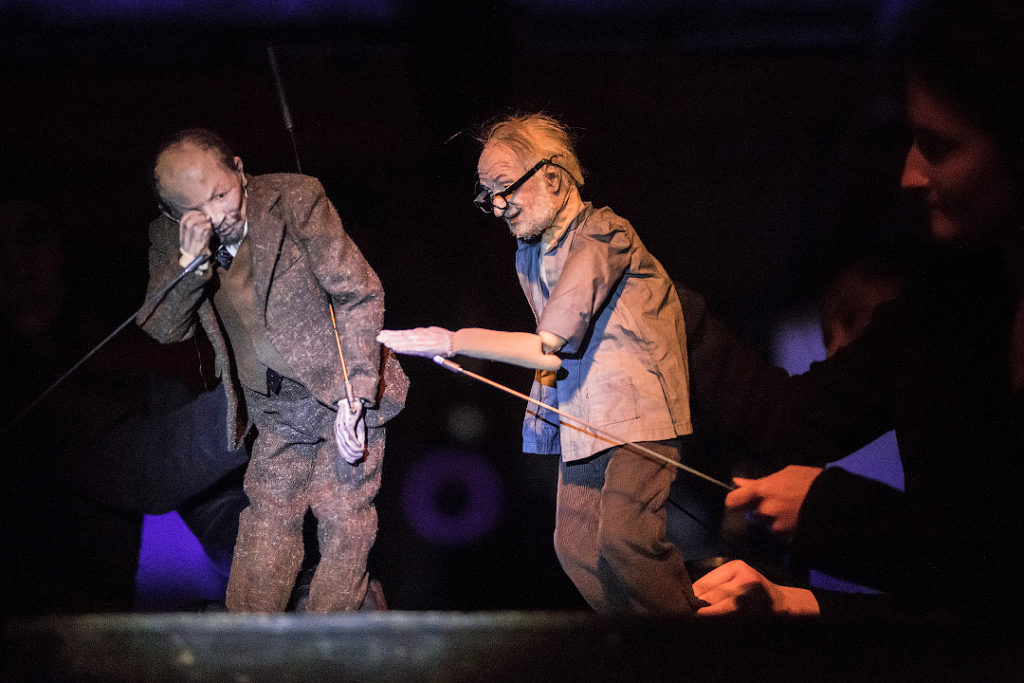

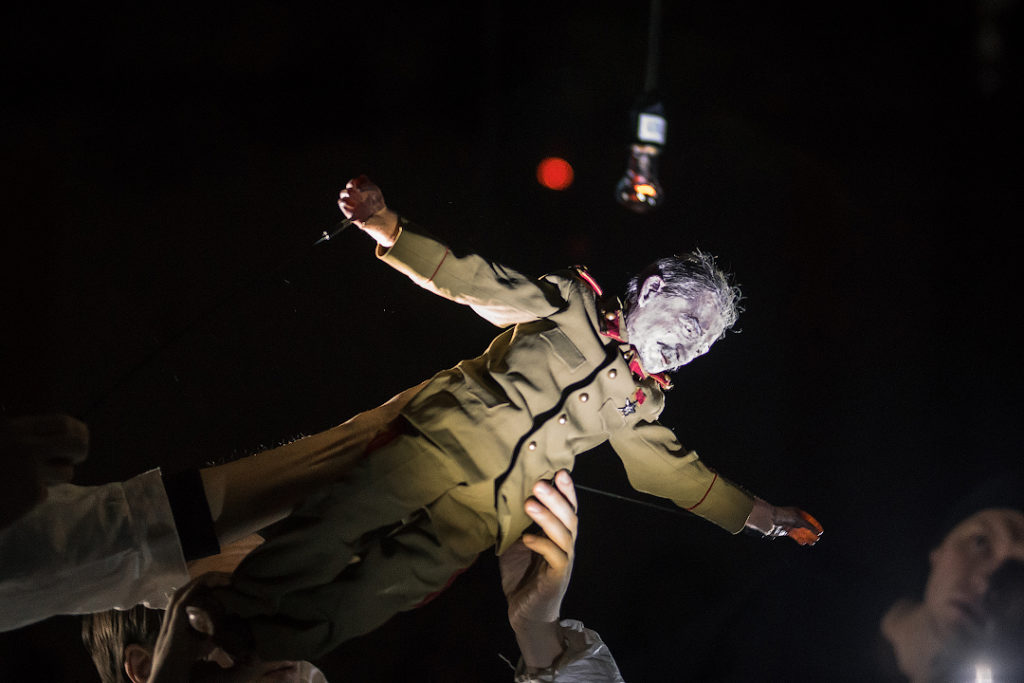

The historical giants Trotsky, Stalin and Lenin appeared several times as little dwarves in the form of three puppets (Suse Wächter), with inevitably comical, but also gruesome effects. They told each other political jokes, climbed up onto memorials to lost heroes, and got the human puppets to dance. In a wonderful episode on the penultimate evening, an encounter took place between Zinoviy Korogodsky, the founder of the theatre, and V. I. Lenin, both conjured up from the realm of the dead, which gave rise to a hysterically funny debate about ideologies both political and artistic.

The two actors Igor Ustinovich and Roman Chusin managed, through improvisation, to create the two figures who appeared in several of the ten evenings as a hysterical pair of clowns, who for example fulfilled Lenin’s wish to lay him to rest in the Moscow Cemetery at last.

Many of the performances included moments with revolutionary visual material; small installations such as a Christmas tree made out of barbed wire and dotted with pieces of flesh; stop-motion animations using propaganda material from the early years of the USSR; a series of scenes directed by Eberhard Köhler with choreographies by Darya Barabanova; Wächter’s puppets discussed different versions of the St Just monologue from Danton’s Death, and were countered by Svetlana Smirnova with the death monologue from Julie; two awe-inspiring teenagers from the movement around politician Alexei Navalny were invited as guests and answered seven questions on the topic of social change, in reaction to which they then put ten yes/no questions to the audience such as: are all Russian civil servants thieves? Or: is the state responsible for your personal welfare?; a day with John Cage’s theatre piece entitled Solo 6 from his Song Books, which was both an inspiration for the ensemble and a novelty for St Petersburg audiences; a reading of an article by the writer Mikhail Shishkin, who lives in Switzerland.

For ten days, it was as though a cornucopia was incessantly pouring forth figures, scenes, stage designs, dances, familiar objects made to seem strange, contexts and perspectives onto a spellbound and fascinated audience, as though it could keep going on like this for ever. The questions that arise above all in the minds of the residents of St Petersburg as they make their way over the original locations of these historical events day by day, were taken up, transformed, passed around, discarded and formulated anew in discussions, lectures, films, montages, personal stories, in fast or hauntingly slow scenes and sequences, poses and dances. The formats that were created might be accessible or intellectually challenging, visual or emotionally charged, but were always incredibly diverse. The productivity and creativity, as well as the sheer amount of effort that the many people involved in these ten days put into their work were astounding and impressive, especially given the extreme spontaneity of the overall concept. The external participants had planned around this block of dates; but the members of the ensemble had to carve out their incredibly committed involvement on a day-by-day basis, for almost no pay, from their normal work and family lives; the next weekend, they were back to performing in repertoire shows. The audience’s reactions showed that they were well aware of these circumstances.

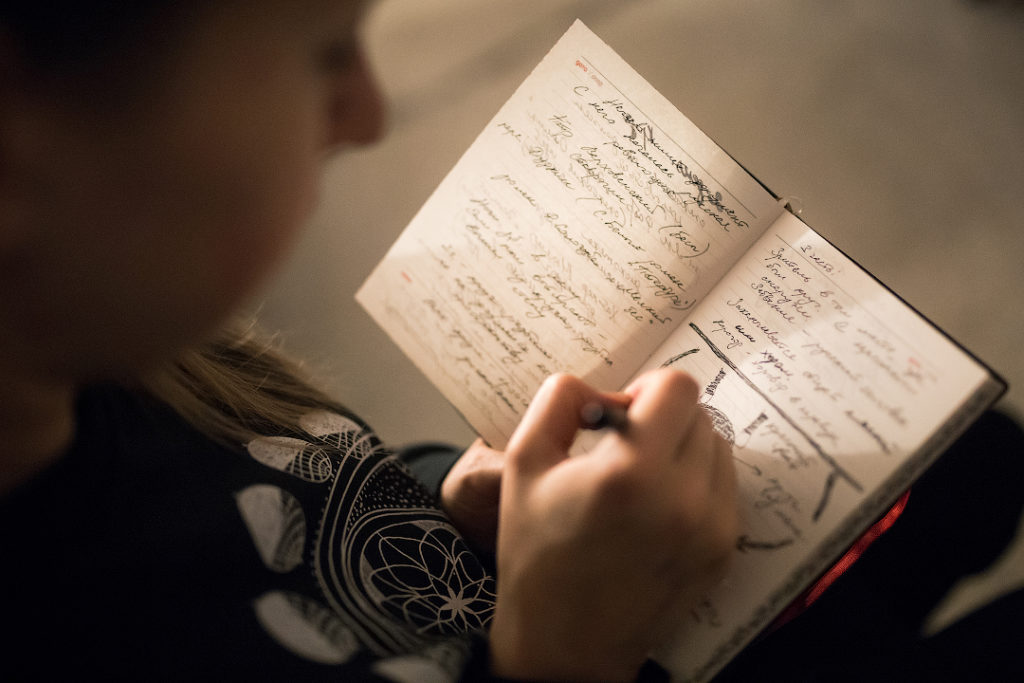

The cycle was fittingly rounded off with an evening entitled белое ничто (White Nothing). The audience sat in front of a white stage area. At the start, a wall was built at the edge of the stage, which enclosed the room and through which the performers would disappear through a door. After 10 minutes, the audience followed the ensemble. In the silent stage area, projected vertically onto a table, the video of an interview of one of the performers with his father about the latter’s ideas of social change was played. Cushions were then handed out in the space, and the audience could take their seats. The ensemble members placed in front of every audience member a wax candle and an empty glass, on top of which was laid half a slice of bread, and into which was then poured a little vodka. No words, no music, just soft footsteps on the stage, the sound of glasses being put down on wood, splashing in the glasses. People got up, drank the vodka and ate the bread. A ritual free of ideology, which touched you without pathos through its concrete acoustics and its silence, and could thus be pleasant and moving.

A bunch of light bulbs glimmered in the middle of the space, the audience was once more made to move in a big circle, an actress carefully placed two handfuls of red tacks into the hands of an audience member, who handed them over to his neighbour, and thus the tacks went on their way, carefully passed on, round the circle. Danila Korogodsky wrote words in white on the white floor (those who were privy to it knew that she was writing a quote from Rudi Dutschke about the utopia of a world without war and famine). Every now and again, the quietness of the pencil writing these words would be interrupted by a tack falling to the ground, until the hands had passed their load once round the circle, and an actress put them into a vase underneath the light bulbs, adding to them three red carnations. The first word of the evening was also the last one of the whole cycle: Спасибо – thank you.

First published in The Theatre Times.

Leave a Reply