Translating Baroque Opera

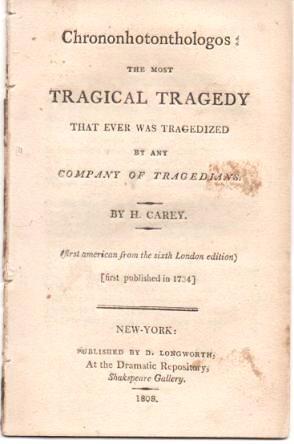

Yanik Riedo and I spend five days at the Translators’ House Looren as part of the weekly mentorship, a young talent promotion programme of the house. Yanik brings his translation project with him, a short baroque opera with the spectacular title Chrononhotonthologos by Henry Carey from 1734. At the title The Most Tragical Tragedy That Was Ever Tragedized By Any Company Of Tragedians, the fun only begins, which is then advanced by King Chrononhotonthologos as well as characters with overwhelming names like Aldiborontiphoscofornio. The play itself is a real find and throws me into unfamiliar territory. In the weeks before the mentorship, I try to get at least a first overview of the circumstances of this baroque period in England and also in Germany, and I am amazed at this period, in which there was at least no theatre system worth mentioning in Germany. As is well known, the German intelligentsia suffered so much from jealousy of French culture in particular, from which so many dramas were imported without there being any German theatrical voices of even approximate quality, that efforts were made to form a German cultural nation with a system of German national theatres showing German plays in German. The German theatre system lived from translations and from the English and Italian theatre troupes, “comedians”, who had been travelling around Germany very successfully for half a century.

Chrononhotonthologos is a nonsense play, but also a political satire aimed at Queen Caroline and her lover Robert Walpole and King George II. Everything happens very quickly in highly dramatic, spectacular scenes in which wars end as quickly as they begin and emotions fly to extremes before promptly fizzling out. About the fast-paced plot: The empire is overrun by the Antipodes – who logically work the other way round, namely walking on their hands – but don’t worry: Chrononhotonthologos scares them away with his sheer gaze. Queen Fadladinida, however, falls for the captured antipodean majesty, who, however, barely eaten in prison, disappears from the scene again.

In addition, there are some dances and songs, and the plot also suggests other, probably artistic, actions at text-free points. At the same time, the text also takes aim at prevailing contemporary theatre forms such as the emerging theatre machinery. The play is written in pentameter and has many passages with end rhymes. Formally, therefore, the play is at the same time rather short, but also a bulging all-rounder.

Something else catches the eye and makes the text a pearl: it anticipates what are today called non-binary identities and non-heteronormative sexual preferences. Women desire to be men while loving other women. Multiple relationships are practised, marriage as an institution is declared a failure.

Yanik’s focus, which directly concerns the translation, also lies on these qualities. Apparently, there is no German-language version yet. Yanik first presents a version in which, by means of gender-neutral pronouns and renaming of many characters and especially their titles (e.g. King/Queen Majesty), any definition of gender disappears. After all, the empire in the play is called – almost unbelievably – Queerumania. With Yanik, the majesties are called Chrininhitinthiligi and Fadladinidi.

Every morning we work in the large room in Looren with a view through the glass front onto the initially misty valley around Lake Zurich. Our efforts on the good working draft are also a matter of keeping the verse metre exactly. Yanik quickly finds really funny solutions here that make the text shine with pentameter and rhyme. Then there are always individual terms that are important, concerning the relationships of the characters to each other, their respective states of mind or simply the information management for the audience. This is very intricate work, but Yanik soon gets the hang of it and works increasingly independently. The fog, both literal and proverbial, lifts during the latter days of our stay, the text and also the view of Lake Zurich and the distant mountains open up more and more. We come to the conclusion that diversity and the play are better served if not everything is lumped together and all gender identity disappears from the play. This is a dramaturgical decision for the production and is reflected in the translation. Together we check the text again and again for inherent coherence and in the process discover ever new surprises that definitely make us want to stage the text as well. It virtually calls for a big drag show with all the registers of the sexy-burlesque. I can’t wait to see it on stage.

Because that is the second part of the work, next to translation: How do I get an independent theatre production off the ground? What steps do I have to take from forming the team to the concept to the cost plan to the application?

My first stay in Looren brings me not only wonderful mountain and valley panoramas but also encounters with dear colleagues, walks up the Bachtel and reunions with some Zurich friends and colleagues. Among others, I finally meet Dipika Arwind, whose PHANTASMAGORIA I translated last year and which is awaiting its DEA at Drei-Masken-Verlag. The short week definitely makes me want to do more: more mediation, more teaching, more Looren, more mountains, more theatre translation.

Leave a Reply